ROSAMOND HARDING

Author & Pianoforte historian (additional text: 14 April 2024)

Rosamond Harding a very familiar name to anyone who has studied the history of the piano.

Her book, published in 1933, The Piano-forte - its history traced to the Great Exhibition, 1851, was so superior to any contemporary study that it was long accepted as the leading publication in this field. Indeed, for some purposes Harding's work remains a useful reference source – for example, her appendix of patents is unlikely ever to be superseded.

But who was the author? Curiosity led me to ask anyone who might possibly have known her, but this proved hopeless. No one claimed to have known her. In the late 1970s her name was still in the membership list of the Galpin Society [dedicated to research into musical instruments] but among their members I could find no one who had any recollection of meeting her. She remained a mystery.

Then, quite by chance, after years without progress, I found a clue in the Broadwood letter files at Woking – a letter she had written many years before to Captain Evelyn Broadwood! Eureka! She wrote on headed notepaper, from Newnham College in Cambridge. The archivist there was very helpful. So, I made a journey to Cambridge, and began the search. After looking through her papers in the college archive, I went that same day to her former homes in Histon, Madingley and Doddington (all three in one day). Later that year, when in Yorkshire, I also took the opportunity to visit her grandfather's former home, at Kirkstall Abbey – actually across the road from the abbey ruins. Walter Harding's home is now a museum – small, but interesting. With an amazing stroke of good fortune, I was able to contact her last living relative in Yorkshire, Mr. E. M. Butler. He had several items that he simply did not know what to do with, including an uninscribed studio portrait c. 1920 that you see below. Indeed he was unsure who the sitter was! (And I had some difficulty.)

This page is intended as a memorial to Rosamond Harding, and a service to readers of this website. Here I am giving only a brief summary. For a longer account, see my paper in the Galpin Society Journal, 2007. (Perhaps one day I will be able to publish a revised and extended version, better suited to a general readership, but no opportunity has yet arisen.)

Here are the basic facts:

1898 Rosamond Harding was born at the rather forbidding Victorian manor house in Doddington, near March, Cambridgeshire, the first child of Ambrose and Adela Harding. Her father Ambrose owned most of the village and, as the only son of Colonel T. Walter Harding, was heir to a large fortune, amassed in the textile trade in Yorkshire. However, Ambrose, did not continue the family business tradition but lived the easy life of an academically inclined country gentleman. He was never in robust health.

1899 Rosamond would have no memory of Doddington. She was just one year old when the family moved to the attractive manor house at Histon, two miles north of Cambridge. Here, in acres of private grounds with a high wall around, Rosamond passed her formative years, effectively isolated from the village community. She was understandably very attached to her father, a gentleman naturalist, whose hobbies included a private zoo of exotic animals, particularly lemurs and tropical birds, which must have been fascinating for a child.

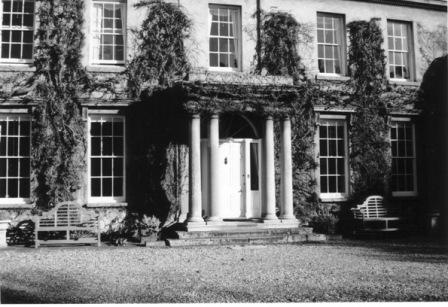

Histon Manor, Rosamond's home 1899 - 1927

Histon Manor, Rosamond's home 1899 - 1927

1906 Her only sibling, Thomas Harding, was born when Rosamond was seven. He was handicapped from birth but the precise nature of his disability is not known. It was quickly recognised that he would not be able to manage his own affairs. The Harding family inheritance would not be his. Rosamond meanwhile attended several boarding schools, but she was always unhappy, so when her parents heard of her tears, and the teachers' dispair, she was allowed to come home, usually after only one or two terms. Ambrose's hope, to give her an education such as her brother would have had, were disappointed. Consequently, she was mostly home-educated by her father. He taught her how to make technical illustrations, with pen and ink, which became such a feature of her piano book. This was a skill he had acquired himself for illustrating his zoology papers for the Linnaean Society.

1917 Rosamond's only experience of the world of work was at the local Chiver's Jam Factory, packing supplies for soldiers at the front during the first World War.

1922 Though she had no formal qualifications, when the war was over she was accepted at Newnham College, one of two colleges for women at the University of Cambridge. There she was to read for a music degree. The college archive contains her personal documents, which is where I discovered so much about her.

Studio photograph c.1920

Studio photograph c.1920

1924 Her undergraduate course was not a success. At the end of her first year (1923) she achieved only a disappointing 'Third Class'. Thereafter she dropped out, left her studies, and never sat 'finals'.

1927 On the death of Colonel Walter Harding, Rosamond's father, Ambrose, inherited Madingley Hall, a splendid mansion built c.1543 — which then became their family home. Rosamond loved Madingley. Here she was in her element, enchanted with the Elizabethan interiors, restored by her grandfather. As a child she had previously visited many times. For example, when Col. Harding had recently completed his restoration of the house in 1913 he held an Elizabethen Ball. Rosamond came in the character of a page holding the train of Queen Elizabeth's gown. The queen was played to her mother Adela – recreating as best they could, the atmosphere of Tudor England. But now, in 1927, Madingley became Rosamond's home, and living there, in historic surroundings, had a profound effect on her outlook. Though she had no qualifications of any kind, in 1927 she was accepted by Prof. Dent and began research for a Cambridge Ph.D., financed by her father.

Madingley Hall, Cambridge, painstakingly restored by Col. T. Walter Harding,

former Lord Mayor of Leeds and great benefactor of that city. [Photo: Michael Cole]

1931 After four years Rosamond had completed her thesis: The Pianoforte - its history traced to the Great Industrial Exhibition, 1851 and she was awarded her Ph.D. Her research had taken her to Berlin, Nuremberg, Stuttgart, and Brussels. She also received much advice from Capt. Evelyn Broadwood. Readers should note that in her statement at the beginning of this thesis, where a student is required to acknowledge any prior sources, she specifically states that for Part 1 (the early chapters dealing with piano history before 1800) she is relying on published material by Edward Rimbault and A.J.Hipkins, though many of the action diagrams drawn by Harding improve on her sources considerably.

1933 A trust fund set up by Ambrose Harding paid for publication of Rosamond's thesis (dropping some illustrations but otherwise with miniscule changes). If her book reads like an academic thesis, that is precisely what it is. It was printed and sold by Cambridge University Press, but Ambrose retained the copyright. Rosamond kept their annual statements from CUP and filed them: I found them in her personal papers at Newnham. She also published the first modern edition of Ludovico Giustini's Twelve Sonatas for Pianoforte of 1732 which, as she rightly said, was the oldest music published specifically for the instrument. A private concert at Newnham College featured Giustini's sonatas, alternating with eighteenth-century English songs, using a square piano by Longman & Broderip, loaned by a friend. She evidently chose this so that the audience, who had probably never heard any piano made before 1850, would have some idea of the tonal qualities of an eighteenth-century instrument.

1936 She joined a local aero club and qualified for her pilot's licence, logging 136 hours flying in light aircraft, during which she reportedly annoyed her father by flying low over Madingley Hall, so that her brother Tom and the house staff could see her waving to them. Her delight in this activity is shown by the fact that she kept her leather flying helmet to the end of her days. It is now in the archive of her personal items in Newnham College.

1937 After four years only 93 copies of The Pianoforte had been sold, which was very disappointing, so she reduced the price from 50 shilings to 30 shillings, but this made little difference. Apparently, very few people wanted this book at any price. She also reduced the price of the Giustini sonatas, but that too languished.

1939 As a qualified pilot she volunteered for war time service in the air, but her offer was rejected, without explanation, as were many other qualified female pilots'.

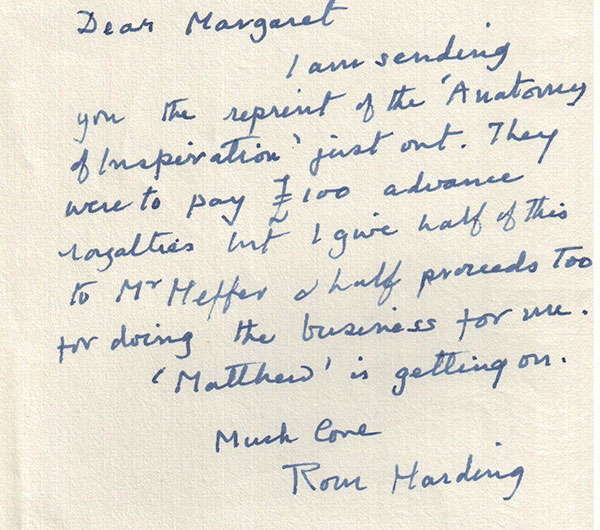

1940 Some women fliers were later drafted in to deliver planes from factories to active airfields, but Rosamond had no such satisfaction, so she volunteered as an Air Raid Warden in Cambridge. She stayed up at nights, on top of a church tower, watching for German planes approaching. At this time, having saved up a fund to buy paper, which was in short supply during the war, she engaged a local printer (a Mr Heffer) to publish An Anatomy of Inspiration. A note in her own hand records that this book was declined by every publisher she approached, and in despair she was going to trash the whole thing. Yet, when published on her own initiative, this was by far her most successful book. Many readers found it thought-provoking and inspiring in itself. The modest initial print run sold out within the year. This enabled her to correct numerous typos when publishing a 'second edition' very quickly. Two more reprints were to follow.

1942 Both her parents died this year, Adela in the spring, then Ambrose in the autumn. The last 4 copies of The Pianoforte were sold at a discounted 14 shillings each, to clear the shelves at the university press. A statement to this effect was among the last letters that Ambrose received. It appears that fewer than 220 copies were sold altogether – further copies in sheets, lying unbound in the storeroom, were destroyed.

1948 After the war she continued to live at Madingley Hall, with her brother Tom and a housekeeper, and Laffling, their faithful butler, but she was subject to her father's trustees. Unhappily for Rosamond, the trustees decided to sell the whole estate to the University in 1948. She was powerless to prevent it, an injustice that she very much resented. Madingley Hall is now used for 'The Department of Continuing Education'. Part of the estate land was used for the American Cemetery, which is today prominently signposted in the area. With the sale contract completed, Rosamond had to leave. She had been mistress of Madingley for just six years. She was heartbroken and, as a friend later wrote in her college obituary, Rosamond never returned until she was carried home in her coffin.

1949 Compelled to leave Madingley, Rosamond rented Icomb Place, a very ancient house dating back to about 1250, in a tiny village in Gloucestershire, near Stow-on-the-Wold. Here she kept her personal collection of ancient musical instruments, but she was now a long way from her beloved Cambridge. She loved the ancient house, but not the location, so far from the university and all she had known.

Icomb Place, near Stow-on-the-Wold. (Photo: Michael Cole)

1954 Her lease at Icomb expired after only five years, so she had to move again. She then sold part of her instrument collection at Sotheby's, in December. This included a square piano of 1769 made by Zumpe & Buntebart, an anonymous Italian Harpsichord (c.1700) with a painting under the lid, and a very fine bass viol by Henry Jaye. (She was working on a definitive 'life and works' of Matthew Locke at this period.) Through the 1960s and 70s she occupied a succession of small, very uninspiring modern houses with her brother Tom, always within easy travelling distance to Cambridge. Laffling's son tells me that she had a smart little sports car for such journeys. A visitor in the 1970s remarked on the strange contrast between her humble modern home, on an anonymous street, and the beautiful antique silver service that she brought out when anyone came to tea. He also noted that her papers were scattered everywhere in apparently chaotic disarray.

1962 Second-hand copies of The Pianoforte had become very scarce, yet thirty years after her pioneering work, interest in the subject was rising. She received several requests from reputable publishers to reprint the work, one even offering an advance of £100, and generous terms thereafter, but she rejected all offers, insisting that she intended to bring out a new, corrected edition herself. This was a poor decision. She was becoming very obstinate.

1967 An Anatomy of Inspiration went through several editions, the fourth being publishedin 1967 to further critical acclaim — it's a very thought-provoking and original book, but not something that brought her any fame.

1973 Forty years after its original publication a pirate edition of The Pianoforte was published by Da Capo Press, New York. Rosamond was not consulted, not paid, and certainly not pleased. It was useless to protest, since American law offered no remedy, but she placed a futile notice in The Times to express her annoyance and disown the publication, stating clearly that it was published without authority, and again saying that she was preparing a revised edition herself. It is ironic that so many American admirers have this edition, unaware of its history.

1976 Her brother Tom died. How much of her time and attention had been taken up by caring for her disabled brother we will never know. When they lived at Maddingley Hall she could call on assistance from the housekeeper or her butler. But when forced to leave there she had to do everything herself (I suppose).

1978 Her long-promised second edition of The Pianoforte was at last published — but it was disappointingly revealed to be a photo reprint with only a few trivial changes. Consequently, many serious mistakes that could be forgiven in a ground-breaking book by a 35 year old were not corrected, and can be seen in her magnum opus to this day. Unhappily, her travels in 1930 did not include Salzburg or Vienna, so Mozart's piano isn't mentioned. The gaping hole at the centre of her work is her failure to give any adequate account of Viennese pianos of the classical period. Nearing 80 years of age, and out of touch with recent research, she was simply not equal to the task.

1982 After living at many addresses in or near Cambridge, Rosamond Harding died at her cottage in Southwold, Suffolk. (A short walk from the seafront, and facing an attractive village green, it is now a holiday home. To locate it via search engines type: Jersey Lodge, Southwold.) She returned to Cambridge for burial, where she was carried through the gates of her much-loved home at Madingley Hall, for the first time since 1948. I could find no grave marker in the churchyard, but I did see that her name was added to the small family monument on the north wall, inside the church. With no surviving family to check on the stone mason's work, her surname was not included, so it reads oddly. Opposite, there is a brass plate on the organ indicating that this was a gift from Rosamond's grandparents in 1908.

Family Monument fixed to the north wall in Madingley Church

1982 By her will, the Victoria & Albert Museum was offered her residual instrument collection, but this offer was declined. No instruments from her collection can be located at present, but presumably one of the known Zumpe & Buntebart pianos of 1769 would have been hers. She certainly owned a very handsome 1812 Broadwood (shown in her book, page 302), and other instruments – but none can now be located.

1989 A posthumous second reprint of the 'second edition' of The Piano-forte was brought out, which is still available from Heckshers and often consulted by students of music — with none of its faults corrected.

2005 Extra Note. When I made a visit to Newnham College, the archivist was very helpful and brought out everything related to Rosamond Harding, allowing me to look through them at my leisure, which was much appreciated. A discovery I made, that I haven't mentioned until now, concerns a scrapbook in which Harding cut and pasted items from newspapers. The items she selected are quite revealing of her inner thoughts. I saw that they featured Golda Meir, newly elected head of state in Israel; Indira Gandhi, likewise in India; and Margaret Thatcher, Prime Minister in the UK. Harding made no comments [that I saw] but her theme was obvious, and her sentiments understandable. In 1939/40 the military administration refused her offers, as a qualified pilot, to serve her country. She had at least two refusals – with no explanation. (She kept those letters.) After the war, trustees authorised by her late father decided that Madingley would be sold. She was not consulted — evicted and powerless. How different if she had been male! Madingley would no doubt have been run down and mismanaged, but that's not how Harding saw it, and felt it. A few years ago I received an email from the son of her butler, Laffling, who had served the family at Madingley. He recalled Rosamond's visits to their cottage, when his father made special cucumber sandwiches with the crusts cut off, and cut into triangles, just as he had at Madingley Hall in years gone by. Her last living relative, Mr. Butler [by name, not calling] told me of a visit to her home (after she was evicted from Madingley) and how he marvelled at the contrast between her humble, suburban dwelling, and the beautiful china that she brought out for afternoon tea.

Return to Michael Cole's Home Page.